China’s history of architecture goes back centuries. The professions of architect, structural engineer and craftsmen was not as highly regarded as the Confucian scholar-official. So, little written knowledge about these trades has survived over the years. Architectural knowledge was mainly passed on orally, in many cases from a father to his son. During the Song period (宋朝 960-1279) structural engineering and architecture schools existed. Already in early times Chinese architects started to develop modular systems for their buildings.

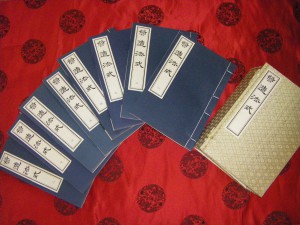

Due to the increased demand for buildings there was a need to set up some valid principles to build faster and with high quality. So Li Jie (李诫) therefore, received the order from emperor Shenzong (神宗 1068-1085) to start the compilation of Yingzao fashi(营造法式), the very first traetise on architectural methods. It’s years later in 1097. The new manual was completed and presented to the throne in 1100 and finally printed in 1103 under emperor Huizong (徽宗 1101-1125).

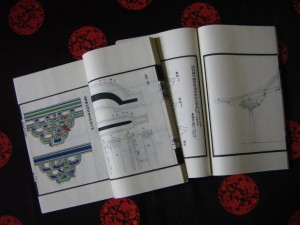

Li’s stated goals were to reduce corruption, because until then there was no proof of quantity and quality of the building materials; and, secondly, to introduce standards in architecture. The treatise had to be used by both the officials who commissioned buildings and the builders who built them. The manual covers topics ranging from foundations to painted ornaments as well as the estimation of materials and labour. Yet, the main body of the work consisted of regulations on the units of measurement, design standards and construction principles with structural patterns and buildings elements illustrated in the drawings.

The Yingzao fashi is the collected summary of architectural history back to the Tang Dynasty (唐朝 618-907). This is the period when the earliest known wooden building, the main hall of the Nanshan Temple (南山寺) of Wutai County (五台县), Shanxi (山西), , was constructed, built 782 AD in full accordance with the prescription laid down in the Yingzao fashi.

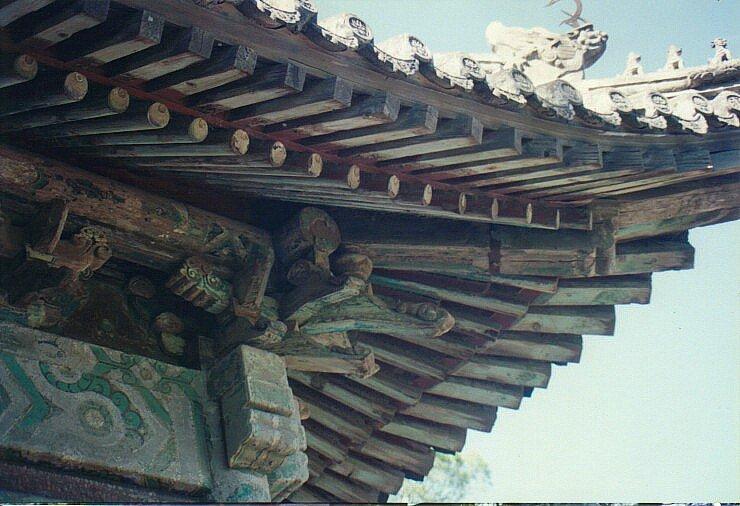

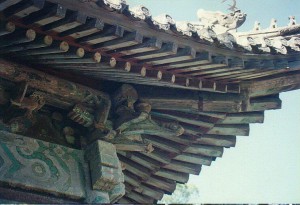

In this work, buildings were classified into three categories. The first category is Palatial Halls. These halls were all large-size buildings, with a depth of eight to ten rafters, whereby one rafter is the space between two columns, sometimes also called bays. The wood structure of halls of this category was composed of columns, corbel brackets who supports in a decorative manner the beam framework. The peripheral (outer) columns and hypostyle (inner) columns were equally long, which brings an outstanding structural feature of the palatial halls.

The secondary category is Halls. The greatest difference to the palatial halls lay in the fact that the lengths of the principal(middle) columns in a hall increased with the rise of the roof, that is, the principal columns were made higher than the peripheral columns by one or two purlin-depths what means more tiles on the roof. The back ends of the extension beams in a hall were also inserted into the principal columns. This type of structure was mainly used for small or medium-sized buildings.

The third category is beam-column structure. Buildings of such a type were usually adopted in galleries, domestic houses and shops , where no corbel brackets were used. Its roof framework was similar to what was later known as the minor-grade woodwork construction.

Another important topic in the manual looks at the columns. Due to the increase of large buildings and the fact that the timber from which the columns are made took several hundred years to grow, the architects had to make use of the small trees and piece them together. Several methods were shown to make large columns.

Pieced beams usually were made of two or three or even more pieces of timber. They were secured by dovetails at the joints and by tenon-and-mortise work inside.

Jointed columns were made up of two or three sections, were joined together by tenons-and-mortises. Mostly no finishing work was done on these.

Encased columns were made from timber of larger size and a number of smaller pieces of wood encasing it all around. Fastening iron hoops were used outside.

Jointed and encased columns were made when a column of an excessive length was needed. It was made first by jointing several sections of wood, forming a core, and then encasing the core timber with smaller pieces of wood all around. Thus it was good in compression strength but weak in bending resistance and was only used for columns and never for beams.

To protect the wooden columns against water and rot, they were set up on a stone base. Because the columns were not rammed into the earth, sitting free on the stone base, the building was flexible in case of an earthquake.

Another method to prevent rotting is painting which will effectively prevent the wood from cracking and rotting.

Painting was not only used as to prevent rotting, but also as decoration and could be divided into two large groups: colourless and coloured paints. Colourless paints are transparent paints, while coloured paints are made up of mineral and chemical pigments. Red, yellow, blue, white, black and green are the six basic colours. Red belongs to the buildings of the throne with yellow tiles on the roof, and set up on a white stone platform. Beneath the eaves the beams were painted in dark green and blue. There is often a gold trim around the dark green.

Althoug just a short look, the real thing provides the reader with the most fascinating book whith over thirty chapters and a whole range of illustrations. Greater in-depth studies would be required to gain a even deeper understanding of this treatise on architectural methods.

This article was first published at Global China Insights No. 02/2014 page 21, by the Confucius Institute Groningen.